Comedy rule of thumb: as you understand more about what the joke refers to, does it get more funny or less funny?

Eg this video made me laugh when I watched it – watch it, it won’t hurt you!

But really when you reflect it simply shows that people don’t all have perfect english language skills, or typing skills, or have dyslexia. It’s most funny when you don’t think and stay in the zone of “wtf????? I can’t even…. who are these people?” (It’s still a bit funny just as a series of inventive nonsense words, mind.)

Many stand-up comedy routines are based on caricaturing people’s beliefs or giving simplified accounts of why they behave/behaved the way they do. “Catholics do x because they believe y”. “Public figure did P, they must be thinking to themselves Q.” To step in and “well actually” would be seen as a humourless move – and in some way’s that’s true, because the joke only works because of the careful positioning of (some of) the facts, and shining a light on it to see a fuller picture sends the shadows of humour scurrying away. So to obey the function of the encounter – spending an evening having a laugh – you have to dampen down that critical faculty.

But there is a cost to this. As this post was sitting in drafts I came across a synchronising article entitled A theory of jerks. The subtitle is “Are you surrounded by fools? Are you the only reasonable person around? Then maybe you’re the one with the jerkitude“, which the author unpacks:

To discover one’s degree of jerkitude, the best approach might be neither (first-person) direct reflection upon yourself nor (second-person) conversation with intimate critics, but rather something more third-person: looking in general at other people. Everywhere you turn, are you surrounded by fools, by boring nonentities, by faceless masses and foes and suckers and, indeed, jerks? Are you the only competent, reasonable person to be found?

To remix that subtitle, you can see that a practice that incentivises being surrounded by fools – like look-at-those-idiots comedy – will jerkify you in time. Going further takes you to a zen proverb, “to set up what you like against what you dislike, this is the disease of the mind,” but we don’t need to proceed that far to see something is wrong.

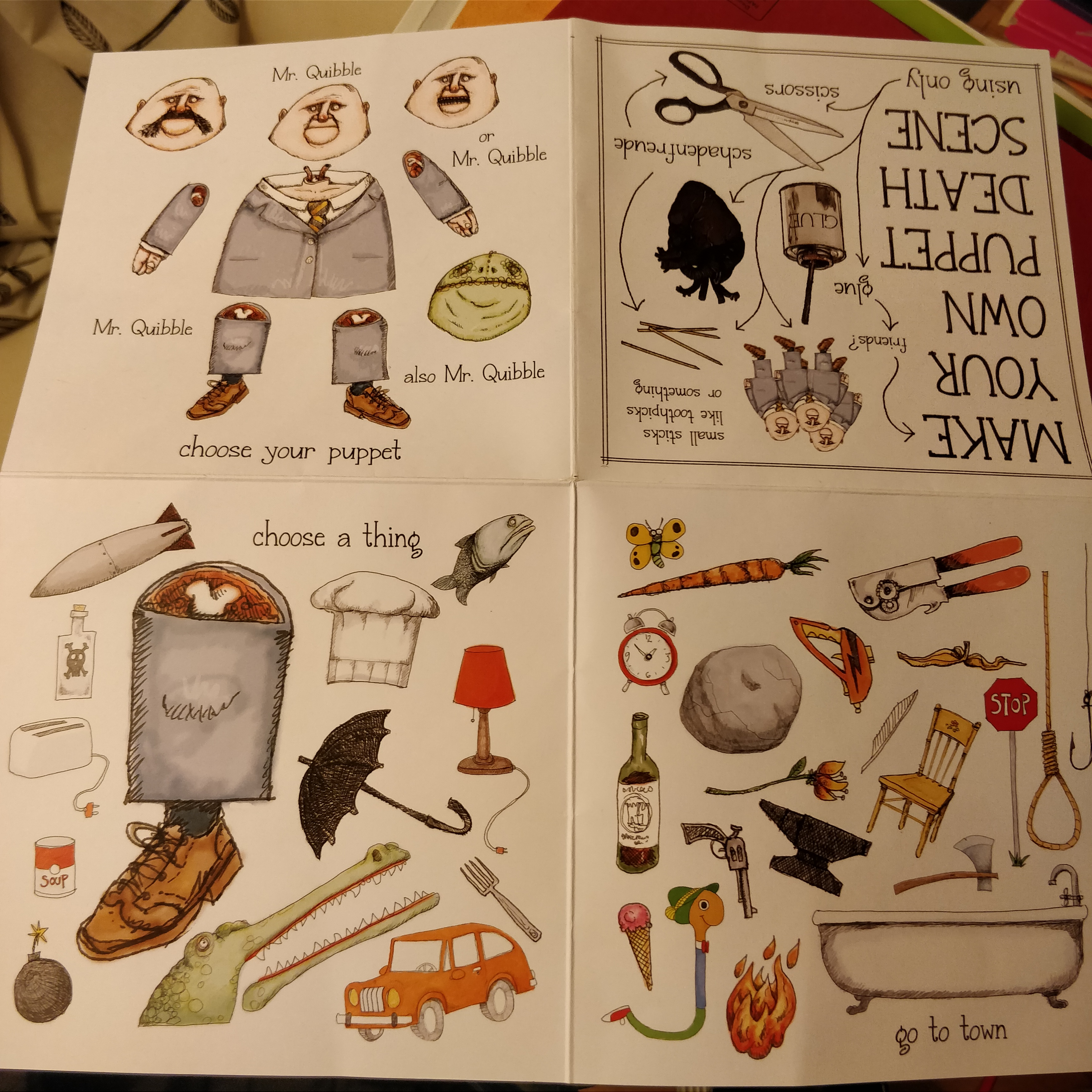

And comedy doesn’t need this at all. Take this scene:

I’ve watched this again and again and still find it funny (and elegant, and poignant). Apart from the ever-present possibility of simple over-familiarisation, there is no air that gets let out of the joke by knowing more. And that’s because it is beautifully specific. There is no rhetorical generalisation involved about a group of people. Generalisations smooth over the details; in some instances that can be a price worth paying, such as sex-based screening for different illnesses, or allocating funding of certain services based on historical trends in areas. But in comedy, we mostly smooth over to make something seem more incomprehensible, dastardly and idiotic than it is, so we can surround ourselves with fools that we stand above (thus playing the jerk). And vitally, the details are where the life is. Here we see an encounter between two figures, not representing “the clergy” and “the outsider” but themselves; we are free to draw conclusions – you could decide that Hackman’s priest reflects benign privilege which doesn’t notice how its preferences steamroll those of the supposed guest – but the comedic edifice doesn’t collapse if we choose not to.

It might appear I’m not comparing like for like, as the earlier points focused more on observational comedy/critique rather than fictionally posed comedic film/sketch. Steven Wright is a good example of a stand-up whose material which doesn’t collapse when you think it through, for example “Hermits have no peer pressure.” Or this: “I was reading the dictionary. I thought it was a poem about everything.” These jokes open up a point of view that allow you to see life freshly, and the humour that sits within existence. If I stop and think about that person, holding onto that point of view, reading the dictionary, I find it funnier and funnier, and more and more amazing, not less.

Of course, if that person, that persona that Wright plays, was more knowing, then the whole thing wouldn’t go. So there is an element of deliberately missing-something that powers it. But the thing that is missing is a willingness to go along with the majority perspective, the willingness to not notice things, to instead smooth over. To generalise over the details. And we as audience are not asked to unsee anything, we’re asked to bear witness, as fully as we’re able to, to that point of view – pure, yes, and maybe unlikely to come across in real life, but not because it is a degeneration of what people believe (a straw man) but a platonic form – a way of thinking in which words are there to be poetic – that existence itself tries to bury.

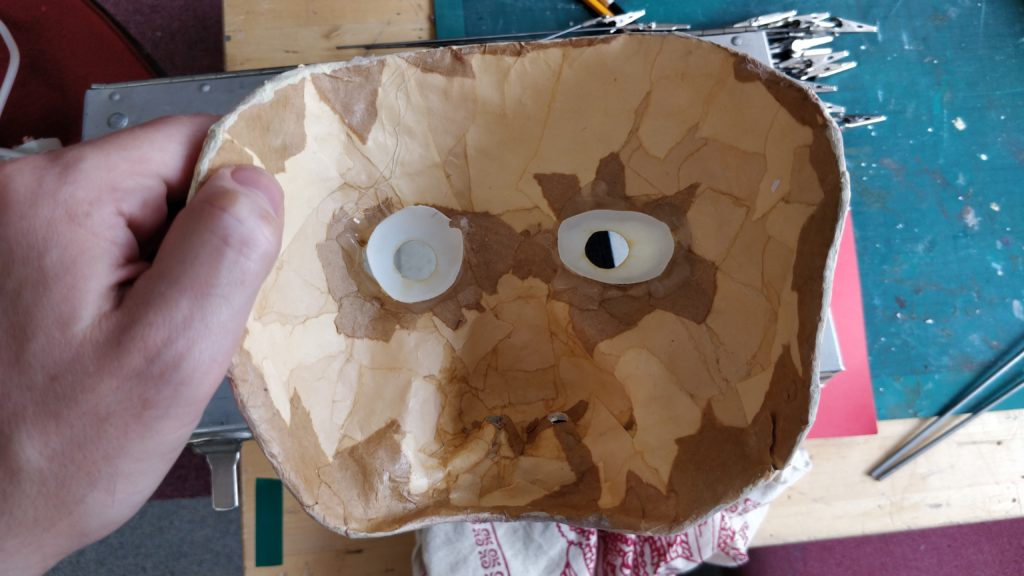

Here’s another case where the joke depends on “not-knowing”:

But again, the not-knowing is inside the frame. We as audience are not asked to make generalisations or draw vague conclusions about why the duo are performing the way they are, conclusions that fall apart on reflection and make it less funny: on the contrary, we have to work hard to keep up. We are called upon to engage in accurate perspective taking, work our theories of mind for all they’re worth, otherwise Lou’s frustration won’t make us laugh. We need to get, even empathise with Lou, for the thing to work – and the more we do, the funnier it is. (Don’t get me started on the naturally reversal.) Again, where this would be problematic would be if it was framed with a generalisation, e.g. “rural people get confused so easily; they are all like…”

Here’s another Wright bit, one that does have an element of judgment toward others in it, but it still works by the rubric above

“I was in a job interview and I opened a book and started reading. Then I said to the guy, ‘Let me ask you a question. If you are in a spaceship that is traveling at the speed of light, and you turn on the headlights, does anything happen?’ He said, ‘I don’t know.’ I said, ‘I don’t want your job.'”

It works for me because Wright does not say “anyone who is incurious about big weird questions is a waste of space”, which might sound satisfying – bammm! – but on reflection I would think about how this thin description of a human being doesn’t account for whether they are a good parent, feed animals, grow their own food, etc. But that’s not quite how Wright delivers the payoff. Instead, he indicates that he himself is the kind of person who could never be satisfied in that context – “I don’t want your job”. He is still living in the specifics, and articulating a personal rejection of 9-to-5 culture, which is entirely consistent with his persona but doesn’t demand that others see it the same way – especially as the persona is presented as fundamentally weird and outside the mainstream.

Still thinking this through. Right now I can say that any comedy that ekes out laughs by generalisations that fall apart on reflection are not my bag.