I try to tell my grief and it all becomes comic.

The Blue Circus, by Marc Chagall.

emergency [g+ backpost]

I took my mum to the theatre yesterday and this happened: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-25458009

We were physically untouched by the event but did see it unfold right in front of us, as we were sitting in the top back of the venue.

Obviously there are consequences of witnessing extreme events. Many people were crying or shaking as we stood outside the theatre and shock was setting in. Luckily I know of some interesting research run by my old friend Emily which you can read about here.

In this instance, my mum was experiencing a higher brunt of the shock than me; in the last year I’ve had a few high adrenaline altercations where I’ve had to break up attacks in the street, so I know the routine… also I think meditation doesn’t hurt for this. I took her to a cinema cafe and, not having tetris present, got us reading through a colourful brochure, discussing films and looking at film imagery. We didn’t ignore the events entirely, but I tried to make sure we didn’t fixate on the traumatic elements. I can thank my doctorate in memory for ramming home how important rehearsal is for laying down enduring memory traces, even for highly vivid events (including, according to some convincing evidence, ‘flashbulb memories‘). So even on the train home, as our thoughts returned to other factors, we kept a copy of a free newspaper on my lap and leafed through all the big photos. Never have the fruits of the paparazzi been so useful!

I’m feeling pretty ok today, and very, very glad that the number of injured is so low, and the death toll looks to remain at zero. It’s still pretty crazy to have witnessed a ceiling of a building rupture and collapse down four levels of theatre in front of your eyes. I guess this is the closest I’ve come to experiencing a genuine disaster – and for that, I can be grateful.

I am glad that I knew enough to occupy my visual scratch-pad and hope that this might be useful to someone else. When I was getting my mum a coffee in the cafe, I noticed a father and son – clearly also fellow witnesses – intensely discussing the events, and introduced myself and my status as a psychologist before giving them the same advice. I hope it was useful to them, too.

About the whole "the internet killed the underground” thing: no, it didn’t. What killed the underground was popularity. Whenever something becomes popular, people surge in and use it for their own purposes. As was written on the Nuclear War Now! Productions forum: “Trues use their social lives to empower the music. Falses use the music to empower their social lives.” It’s that simple. When something becomes popular because it’s rebellious, the herd shows up to take part and use that “authenticity” like currency for their own needs. That adulterates what is and it becomes obliterated (although good people like Alan Moses and Andres Padilla keep the tradition alive! Heroes, if you ask me). The only solution is to rediscover the spirit of the past and apply it in any direction possible. You cannot imitate it from the outside-in; it must be from the inside-out. If this reeks of occultism to you, it should. This is esotericism, and it is the guiding philosophy of humankind anywhere that popularity has not already obliterated truth.“

Thoughts on genre

Western stories aren’t about big hats and chewing tobaccy and slurring. Improv Western scenes often are! And that’s fine, you can have a beautiful scene playing around as cowboys, sending the genre up or, to my preference, sending ourselves up and revelling in the joy of clowning around with a bunch of scene-toys. But it won’t be a Western story so much as a Tribute to, Pastiche of, or Playing About in the Western genre. This post concerns my thoughts on improvised stories in a genre.

Learning genre well involves getting into the guts of what makes that kind of story stick. I believe it’s better to focus on the audience’s experience than the workings of the story itself, which is why I say ‘make it stick’ rather than ‘make it work.’

Noir stories stick with me when they show the consequences of good people making bad choices and how people can be swept up by forces bigger than them. In contrast, adapting something in our given reality and exploring the human condition is how a sci fi story sticks with me. And a Western sticks with me when it shows compromise and hard decisions, underpinned with an examination of honour and how much it is actually worth. (It’s often, but not exclusively, also an examination of masculinity.)

You will probably find that some of the things that make science fiction, noir or westerns stick with you are different to what makes them stick with me. Great. This isn’t prescriptive. If you play with a group you will need to hone in on what resonates for all of you, but your Zombie Survival show may – should – have very different priorities than the one playing down the road.

There are also efficiency benefits of learning genre; Katherine Weaver (of Impro Melbourne) spent some time in her Supernatural workshop on honing investigation scenes so they aren’t boring and expositional. Essentially, there are some ‘necessary’ parts of a genre that easy to deliver in a cliche’d or boring way, so why not delve into how to keep these engaging?

For me? I don’t have a yen to do a show within a genre, but I see the value of soaking some genre instincts into these improv bones. In improv, we can go anywhere – any story is possible. But in practice, human beings are heavily bounded in how we think, behave and react. Without knowing it, we’re playing a genre, except it has no name and so we can’t even see that we’re within its limits. Worse, these limits might not even be our own, but inherited from the first ten improv shows we saw, which were inherited from the first shows they saw…

Genre is good because it dictates a specific sensibility for your scenes, your shows. What does it feel like when your ‘mean’ character doesn’t come good at the end of the show, but remains a prick? What does it do for the story, and what does it feel like for you? Difficult? Then it’s worth doing some more, until that choice feels as effortless as any other. Developing human freedom (as Luke was talking about recently)…

That said, at the moment when I start an improv show I want anything to be possible that night. And it’s true that imposing genre gives you rails of a sort. Isn’t there a risk of settling into the rhythm of the genre, and starting to switch off?

It’s possible, I guess. But why not keep moving: learn a genre well, then try something else, as acclaimed Austin group Parallelographophonograph do?

At its best, genre gives you a shared language, and through that a freedom to treat offers differently. You understand that when your partner sighs and says “Jebediah, I loved those horses as much as you did but that fire was 5 years ago” this sentence offers an invitation into a certain kind of territory, of longing and not letting go of the past, exemplified in the Southern romance genre (maybe? Not my genre).

This is the internal promise between players. This is the moment where you and your partner lock eyes and say “ok we’re not going to ignore this, but neither are we going to resolve it just now. This is the thing we can return to in fifteen minutes and boy the weight it will have”.

The marvellous thing, of course, is that this is a Schrodinger’s moment, where multiple possibilities are alive or not-alive. You can look at your partner and say ‘Deke, though, the thing of it is, this newspaper report… it’s the exact same way our stables burned. The exact same way.’ Now we’re in conspiracy, and that’s cool too. It’s a kind of semiotic dance, where each offer is a sign that can elicit many signifiers. Genre gives us some scaffolding, so when we decide to go for one, we understand some of the avenues it opens up (mining themes of isolation and human frustration, or themes of secrets and terrible acts justified), and can play down those avenues for a while, rather than thrashing about in our heads worrying about plot. The less time we spend worrying about plot, the better.

So, genre.

A sensitivity to certain kinds of impressions we can leave on the audience.

A way to coordinate between players especially in a longer piece, so bits of resonant platform can be named and then put aside as potent features to return to.

A way to make every signifier rich: taking one option rather than another presents tons of possibilities, in-tune with one another, rather than a ‘shit, how do I solve this’ conundrum.

And, finally, a choice: we’re playing in a Southern romance until we’re not, until something is there that we want to follow instead, and suddenly we’re in the mad head of one character and it’s Kafka for the last act.

More words coming

Been quiet here recently. Check out the make shift site for a general update. October involved a lot of impro – the Würzburg festival was effectively triple-length as it also hosted the International Theatresports Conference.

I took some genre/tonal workshops that prompted me to finish a post on improv genre. And spending an extended period in the Keith Johnstone philosophy of improvisation, which is where I begun, got me to reflect on the UK scene a little. So, more words coming.

drones funding LGBT [g+ backpost]

“Thrasher highlights that many of the biggest donors to the Human Rights Campaign, the multi-million dollar nonprofit that receives the bulk of donations for LGBT issues, are drone manufacturers. These donors profit off of the United States’ use of drones to kill civilians, including children, with little oversight or accountability. Drone manufacturers are far from the only ethically dark gray to black donors to LGBT advocacy organizations: a brief perusal of any major LGBT organization’s list of donors reveals that corporate black hats like Bank of America, BP, Coke, and Nike all provide major cash to LGBT nonprofits.

“And it must be acknowledged that these corporate dollars do some good: programs that encourage the leadership development and empowerment of LGBT young people, the election of LGBT public officials, and advocacy for greater research into LGBT issues would be practically impossible in the modern economy without significant corporate donations. Yet there is something antithetical about a movement for equality and justice funded by the forces in the world most responsible for widespread economic and social inequality.

…

“Progress for LGBT people means nothing if it comes at the expense of others also marginalized and fighting for justice. Gay advocacy paid for by companies that poison the land, treat their workers unfairly, and assist in the killing of children from other nations is worthless in the long run. If we truly want a world where LGBT people are equal, we have to recognize that such equality is contingent upon justice for all people.”

Storytelling without dialogue. It’s the purest form of cinematic storytelling. It’s the most inclusive approach you can take. It confirmed something I really had a hunch on, is that the audience actually wants to work for their meal. They just don’t want to know that they’re doing that.

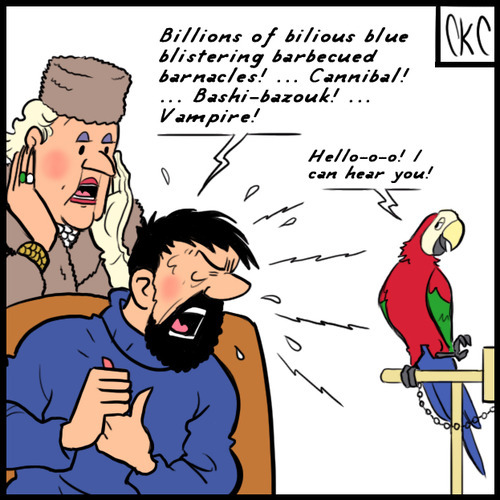

The Castafiore Emerald

A story that really made an impression on me is The Castafiore Emerald, a comic book and one of Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin. The story concerns a weeken gathering at the house of Captain Haddock, Tintin’s pal who features in most all of the later adventures. Along the course of the book, many character’s we are now familiar with show up, and we spend a long time figuring out when the action happens.

Hergé’s works are all page turners, with a lot of attention paid to making the final panel of each two-page spread contain a seed of mystery or a big reaction to something we don’t yet understand, and it’s never been used better than in this book. Why? Because time and again, we think we are entering into the ‘point’ of the book, where the adventure begins, but it turns out to be just a minor moment of life – someone dropping a tray, or an annoying animal bothering someone. Gradually, a central mystery develops, but even that, in the end, turns out to be misleading.

Hergé plays with the form in a stupendous way. Is there a crime? Is there a villain? Can we enjoy the book if not?

And the first time I read it, the answer was: ‘No!’ I found the book disappointing as I was a kid who was after fisticuffs with bad guys and grand adventure. It stuck with me as the Tintin that didn’t. But it’s the one I come back to again and again, and marvel at what it achieves. The book survives on the characters and relationships – and to do that with minimal text and continuing within the style that had been so focused on adventure plots – is really great. In a way, it’s what Seinfeld always aimed for: a show about nothing.

(Posted this as part of the iversity course I’m doing on the Future of Storytelling).

Do you wish to be great? Then begin by being. Do you desire to construct a vast and lofty fabric? Think first about the foundations of humility. The higher your structure is to be, the deeper must be its foundation.